The Night-Case Before Christmas

So, the harvest is upon us, and Samhain (Sow-en OR Sah-wen) is almost here. The days are shorter, the air is cooler, and we’re all enchanted with the scents of falling leaves and pumpkin. Yes, it’s time to talk about Halloween. But tonight, we’re covering a stop-motion musical classic that was born from a love of two holidays: Halloween and Christmas. In fact, if you ask anyone whether this film is a Halloween or Christmas movie, you might spark quite the debate.

Released on October 13th, 1993, The Nightmare Before Christmas gleefully celebrates everything strange and wonderful about Halloween. The film immediately introduces the audience to a horrid cast of characters: personifications of our deepest fears, happily singing in friendly unison: “I am the clown with the tear-away face; here in a flash and gone without a trace! I am the ‘who’ when you call, ‘Who's there?’ I am the wind blowing through your hair”

Brought to life by a powerhouse team, led by Tim Burton, Henry Selick, and Danny Elfman, the film follows Jack Skellington, the pumpkin king of Halloweentown, as he faces issues with burnout and his own identity. Jack’s purpose in life becomes reinvigorated when he discovers Christmastown, and attempts to give this new holiday a try instead.

Outside of its holiday connections, this is a movie that has inspired audiences for almost 30 years. So, goblins and ghouls, let’s talk about Tim Burton’s

The Nightmare Before Christmas!

The Spooky Beginnings

You may notice that the movie is officially referred to as, “Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas.” Burton was the person who created the concept of the movie.

Growing up in Burbank, California, young Tim Burton was fascinated by the Halloween and Christmas decorations in the local stores and shoppes. For years, as a joke, he would place Halloween decorations on his Christmas tree. He thought the holidays clashed in an interesting way, and it was funny seeing them mashed together.

For years, Burton built on that idea, imagining a story told in the tradition of classic Christmas specials like How the Grinch Stole Christmas and the Rankin and Bass Rudolph the Red-nosed Reindeer, but about Halloween.

After attending Cal-Arts, the school notable for uniting many famous animators that would go on to work for Disney Animation and Pixar, Burton worked on The Black Cauldron and The Fox and the Hound.

He later said that it was a struggle to animate in the style of a classic Disney film, especially with “Disney eyes.” Making cute, cuddly creatures was difficult for him, which was why he would eventually move on from the animation department.

He also started working on his own side projects, one called “Vincent,” narrated by the incredible Vincent Price; and the original “Frankenweenie.” Vincent can be seen in the video above.

During this time, however, Burton developed the idea for his own movie even further. He wrote a poem, “The Nightmare Before Christmas,” as a twist on the first line of the Clement Clarke Moore poem, “A Visit from St. Nicholas.”

This original story was the bare bones for the film, following the character of Jack Skellington as he attempts to take over Christmas--we can see how Dr. Suess’ Grinch really influenced this part of the story, with the rhyme scheme and subject matter--Jack Skellington was meant to be a reverse Grinch.

There’s even a 2-D animated version of this poem, performed by Christopher Lee! We will link to it in the blog so you can watch it for yourself: https://youtu.be/XbPCwc_Cdz0

Tim Burton shopped the idea around, but because animation wasn’t a very popular medium at the time, many places didn’t seem interested. Remember, this was still the Bronze Age of Disney, and the studio itself was danger of closing down.

Burton remembers that some people were interested in the idea, but weren’t sold on stop-motion. Stop-motion is much more popular today than it was in the 1980’s, and that’s really saying something.

But Burton didn’t feel that this story could be told any other way. He felt that there was a magic to stop-motion, a reality to it. It had the realism of live-action with the creative freedom of animation.

In the mid 1980’s, after creating his live-action short Frankenweenie, Tim Burton directed his first full-length feature film: Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure.

This movie was huge for Tim Burton’s career, not only because it was a major movie, but because it was the first collaboration between Tim Burton and composer Danny Elfman!

Elfman was a rock artist before he composed films, and he felt like he had no idea what he was doing.

The two men continued to collaborate on films like, “Beetlejuice,” and “Edward Scissorhands,” and when Tim Burton brought the idea of Nightmare Before Christmas to Elfman, Danny embraced the idea and ran with it.

The Songs

According to Burton and Elfman, the songs came first. Neither of them had ever done a musical before, and they didn’t want grand, show-stopping numbers, but instead something like a “Three Penny Opera,” where the plot continues through the songs.

Danny Elfman remembers that when Burton would come to him with new ideas for characters and plot, he would push Tim out of the room because the melodies were popping into his head and he needed to write them down before forgetting them.

Although Elfman is credited with writing the melodies and lyrics to the songs, he says Tim Burton deserves a writing credit for all the ideas and lines that he contributed.

The songs were written long before any scenes were shot, or even before there was a screenplay! The movie was structured around the songs, as each song signified one part of the plot.

Elfman felt a personal connection with Jack. At the time, he was in the band Oingo Boingo, and he had started branching out and doing scores for movies instead. He said that the song, “What’s This,” was slightly inspired by his own feelings at the time, where Halloweentown was playing in the band, and Christmastown was the new world of film music.

Because of this, and the fact that Elfman had written the songs himself, he approached Tim Burton and requested that he be the singing voice for the character.

Elfman said, “I realized that I was writing a lot from my own character. I went to Tim and said, `I'm not the best singer alive by a long shot, but no one's going to sing Jack Skellington better than I am.' And he agreed.''

Long after the songs had been written and the film was shot, Elfman also had to piece together a score. He later referred to it as a sort-of jigsaw puzzle.

He needed to work the songs into the score without giving too much of the melodies away, and they needed to fit together seamlessly. Musicals often alert audiences to an upcoming song, and although he had never scored a musical before, he was able to connect the songs with transitional music so no number was too jarring.

Elfman said it was a challenge--but not in a way that made him want to give up. It was challenging in a way that made him want to try even harder, and even more excited about the project.

The limited orchestra recorded in a small space, giving the tracks more of small-scale sound. This lent itself more to the operetta sound that Elfman and Burton were looking for.

The Director

After years of concept art and sketches, it was time to start putting the animation team together.

Tim Burton had a visual consultant named Rick Heinrichs reach out to Henry Selick as the possible director of the film. Burton knew of Selick because of his recent work with stop-motion (for example, the Pillsbury Dough-boy commercials) and also because they both graduated from Cal-Arts.

After seeing the concept art, Selick happily agreed to do the project. He was giddy, in fact, and Tim Burton trusted his skill and vision so much, that he allowed Selick to be the sole director of the film.

Danny Elfman handed over the first completed song, “What’s This?” to Selick, and the crew started storyboarding and building sets and characters for the number. It was the first sequence shot in the movie.

Selick had his own team, from years of stop-motion animation, and he brought them onto the film with him.

In the Disney+ series, Prop Culture, host Dan Lanigan asked Henry Selick about the pressure he felt as a first-time director on Disney’s first ever stop-motion film.

Selick explained that he didn’t feel pressure at all. Because Burton had so much faith in Selick, he was a little more hands-off than other producers, which gave the team creative freedom to explore concepts and ideas.

On the DVD audio commentary Selick said, “I never doubted that we would be able to figure everything out. I just wasn’t worried. I think I believed in the project so much that I assumed that things would fall into place, and 90% of it did.”

Selick’s impact on the film is immeasurable, but one of the things that he brought to the project that set it apart from other stop-motion at the time, was the moving camera shots.

In stop-motion, we always think of cameras sitting in a fixed position on the tripod while animators manipulate the characters in front of them. So you can imagine that moving camera shots would be technically difficult to pull off.

However, this special touch added a cinematic quality to the movie, with a dynamic energy that many other films in the same medium lacked.

Thicc Sally

Animation

Overall, the animation took three years and over 100 artists and technicians to complete.

Characters

Each character started with a metal armature, that was covered in foam latex by professional sculptors.

Many of these armatures were built by legendary visual effects artist and stop-motion animator Tom St. Armand!

Armand has created armatures for many other stop-motion films, but also live-action films with stop-motion sequences and special effects.

For example: Honey, I Shrunk the Kids; The Rocketeer; and Jurassic Park.

He and Tim Burton both reference Ray Harryhausen as an early influence on their work!

After the characters were sculpted, the puppet fabrication department painted and clothed them as-needed.

After Jack Skellington had been created, the animators had to send the test of his armature to Disney, to prove that the character would translate well on the screen.

Originally, Jack was meant to wear all black, which proved to be a problem because he was too thin and wasn’t showing up on camera. So, Henry Selick decided to try pinstripes for him instead, and it worked very well.

They did this test with Sally as well. The animators wanted her to have quaky, doll-like movements, but they ultimately decided that she looked drunk, and they stabilized her.

In her concept art, Sally was, shall we say, Thicc. She wore a black and white striped dress before it was ditched for her classic patch-work dress.

There were about 200 puppets, many of them duplicates of characters. There were 400 different Jack heads, with separate eyepieces.

Jack was the first Disney leading character without eyeballs, so it was really important that the animators make his face as emotive as possible, so audiences would connect with the character.

Disney reportedly asked them to give Jack eyeballs, but the animators stuck to their guns--they thought it was an interesting challenge to make him lovable without eyes.

Sally also had replaceable faces, since the animators didn’t want to re-make her long, red hair.

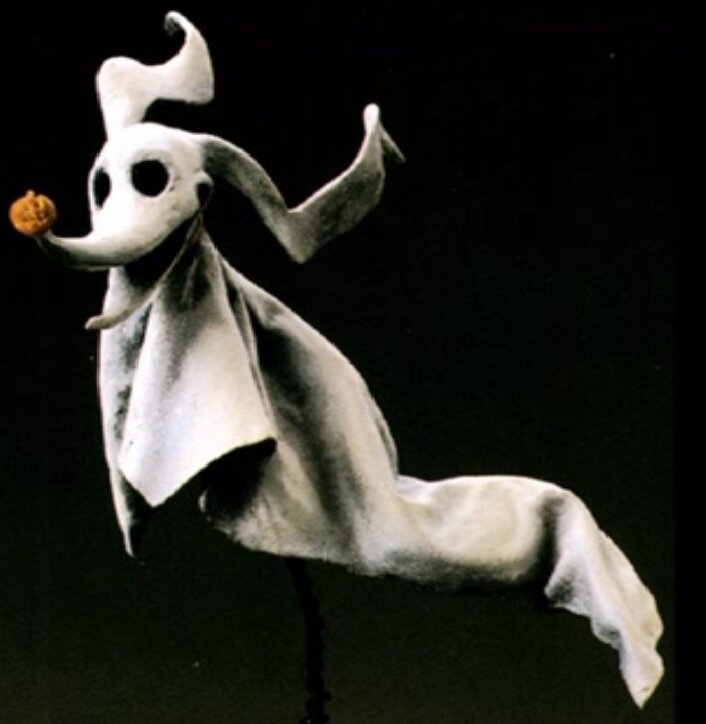

Animators used special techniques for the more ghostly characters! Rotoscoping, the technique of tracing over live-action footage to mimic realistic movement, was used for some of the ghost characters.

One of the most interesting characters in the film is Zero the ghost dog. He was created using a tool called a beam splitter, which is used to split a single beam of light into two, thus giving Zero his translucent appearance.

Example of Edward Gorey’s Work

Example of Ronald Searle’s Work

Set Design

Overall, the movie had 230 sets, filling up 19 sound stages. Some of the sets were lit with as many as 20-30 lights.

There was a very simple color pallet for Halloweentown: Black, Orange, White. Tim Burton didn’t want any deviation from those colors, giving the town the bleak atmosphere of late fall and early winter.

For the Halloweentown sets, production artists took inspiration from the drawings of Ronald Searle and Edward Gorey.

Animators used styles that would call back to the cross hatching done in these drawings.

For example, they would use clay or plaster on the sets and scrape them to give an etched look.

Each set was first created at a quarter of the size first, so the artists could figure out where the sets should break so they could stand between them and reach the puppets for adjustments. When they weren’t able to make a clean break, trap doors were installed on the sets so they could open them and adjust when needed!

It took about two years to build the sets.

One of the most iconic pieces, the spiral hill that moves with Jack in the song, “Jack’s Lament”, was built more than once. There was the stationary hill that was later covered in a foam substance to give the appearance of snow--and the mechanical hill built with its own armature to move as Jack walks across it.

Henry Selick said that it just felt right that the hill would move, but Tim Burton had told Selick that there was to be no magic in Halloweentown.

Selick got around this by saying that the hill is mechanical. So, in universe, that is a mechanical hill reacting to Jack’s movements, not magic.

Movement

Overall, there were about 12-17 animators, and eight different camera crews tasked with capturing the animation.

Every form of animation takes a little bit of acting, because animators need to understand the motivation behind their characters’ performances in order to draw them well.

But, with stop-motion, each animator is essentially putting on a performance through their puppet. This is something Henry Selick understands and tries to get from his animators while directing. On the DVD commentary for this film, he said, “In the end it’s an animator and their puppet and they have to breathe an actual performance into that puppet one frame at a time.”

Selick himself became the “actor/animator” for Jack.

So, Tim Burton created Jack, Danny Elfman gave him his soul, and Henry Selick brought him to life. In their own ways, all three men saw themselves in the character, which would explain how Jack resonated with fans as well: he was completely authentic.

Selick based Jack’s movements on his character design, and the movements of spiders and stick bugs. He also used Fred Astaire’s elegant dance moves as a reference as well!

Animators did 2-3 test shots before Selick would sign off on the movement and acting before the final shoot was done. It was so meticulous, that one minute of film took an entire week to shoot.

The Screenplay

Horror writer Michael McDowell had previously worked with Tim Burton as the screenwriter for Beetlejuice, and actually started working on a draft of this film’s screenplay.

However, he was too ill to continue working on the project, and the screenplay was taken over by Caroline Thompson.

Thompson was actually Danny Elfman’s girlfriend. And at the time, she had heard every song in the movie, which made her the perfect person to write a story that connected them.

According to the DVD commentary, McDowell still made contributions to the story, like Sally’s tendency to break apart and piece herself back together. However, in the Disney+ series Prop Culture, Thompson says that she immediately elaborated on this idea, and pictured a scene where Sally would use her disembodied leg to seduce the villain, Oogie Boogie.

Caroline Thompson wrote the new script in about two weeks time, and was not required to make any major edits or re-writes! She received a few notes from Burton, but her story appeared to perfectly hold the film together, filling in all the gaps.

Thompson’s biggest contribution through her script was Sally’s personality and development. Sally went through a couple transformations throughout the film’s process--from the “babe” in Burton’s drawings, to a shaky rag-doll designed by Rick Henrichs, to a soft-spoken, yet strong and independent character that is an absolute hero behind the scenes of Jack’s shenanigans.

Although Sally may at first appear to be weak, she has identified her strengths and attempts to use them to stop Jack and undo the harm he has caused.

Thompson is proud of her contributions to the story, as she should be.

Voice Acting

In stop-motion, the voice acting is done first. Many of the songs were animated before the final voices were added in, so it actually took a year of going back and re-shooting scenes with new singing voices to match them perfectly.

Chris Sarandon provided the perfect speaking voice for Jack Skellington.

Serandon also acted in “Dog Day Afternoon,” and “Fright Night,” but he’s most well-known as the evil Prince Humperdink.

Serandon has never actually seen or touched a Jack sculpture until appearing on Prop Culture, when he got the chance to look at the character.

He still gets recognized for playing Jack, which is great news for someone who portrayed such an iconic villain as Humperdink.

Danny Elfman, of course provided Jack’s singing voice, but he also voiced The Clown with the tearaway face.

Catherine O’Hara voiced Sally! She had previously worked with Tim Burton on Beetlejuice just a few years earlier, however she is also known as Kate McCalister in Home Alone, and most recently Moira in Schitt’s Creek.

William Hickey played Evil Scientist, Dr. Finkelstein, and he was also known for playing Lewis in National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation, as well as Grandpa Wrigley in Pete and Pete.

Finklestein’s lair was modeled after his character. If you look closely, Jack’s house is modeled after Jack as well, and Santa’s workshop is modeled after Santa Claus!

Glenn Shadix played the Mayor of Halloweentown, and was also Otho in Beetlejuice (the interior decorator.)

The mayor’s design was meant to point out the two-faced nature of politics.

Lock, Shock and Barrel were voiced by Paul Reubens (AKA Peewee Herman), Catherine O’Hara, and Danny Elfman respectively.

The three were inspired by a Twilight Zone episode that Tim Burton saw as a child. The episode featured characters that wore masks--and when they removed their masks, their faces were the same. It was a creepy image that stuck with him throughout his life.

Ken Page played the evil Oogie Boogie, and he was also known for All Dogs Go to Heaven and Polly! (1989)

In a deleted scene, the identity of Oogie Boogie turned out to be Dr Finklestein! Through his dialog he explained that he was angry that Sally loved Jack more than him, he was her creator.

In the final cut of the movie, Oogie Boogie is made up thousands of bugs, being controlled by the single Boogie bug that gets squished at the end of the movie.

There was meant to be a scene where the bugs danced as well, but the animators found it to be too meticulous to make it happen.

There was also another deleted sequence of Oogie Boogie’s shadow, dancing on the wall, but it was cut for time.

Edward Ivory played Santa, and this was his most well-known role.

Santa’s voice can be heard at the beginning of the movie during the initial narration. Since the narration doesn’t return, it makes sense that it turns out to be a character in the movie, though this is not immediately obvious to the audience.

Reception

The Nightmare Before Christmas was technically made by Walt Disney Studios, but they released the movie under the Touchstone name, for fear that it may hurt their animation brand.

Disney was in a precarious position at the time, as they were trying to decide whether their animated films should be made at other studios (for example, should they allow PIXAR to make Toy Story?)

They also didn’t know how to market the movie, and because of this, it wasn’t a commercial blockbuster. It made money, and it was by no means a flop, but it’s true success would happen in years to come.

Although The Nightmare Before Christmas is not truly scary to anyone but really small children, Steven Greydanus in the Catholic Digest from 2014 had this to say, “The frightful or creepy galvanizes us. It speaks to us of mortality, of the moral and existential implications of the kind of beings we are: creatures of frail flesh and eternal spirit, alienated from our world and from ourselves, haunted by dreams we can’t attain and dread we can’t escape.” Surprisingly, he went on to say that it is for all ages.

Cult Classic Status

In 2005 it was adapted into a video game by the art director Deane(Pronounced like Deen) Taylor and Tim Burton. It was made for the Playstation 2, X-box, and Gameboy Advanced.

On October 20, 2006 it was reissued as a 3D movie in theatres. It also came with a new CD that had the original songs with bonus tracks that paid homage to Danny Elfman’s scores. Some of the artists that contributed were Fall Out Boy, Panic At The Disco, and Fiona Apple.

Sales in toys/blankets/cups/etc.

You can find anything you want related to this beautiful film. Clocks, mugs, storage jars that say Frog’s Breath and Deadly NightShade, cookie jars, jewelry, and so much more.

The Nightmare Before Christmas was the result of 20 years of ideas, drawings, and collaborations, culminating in an animated classic that will last for generations. It gave Henry Selick his first full-length directing job, which paved the way for James and Giant Peach and Coraline. It gave Tim Burton the opportunity to make animation in a new way--his own way--that he wasn’t able to do before.

The realism with stop-motion moved audiences, and the fearlessness that this film had with its macabre imagery made it ground-breaking. It teaches lessons about passion and arrogance, and knowing your own strengths and weaknesses. This film spoke to children in a way that animation rarely did before, and helped popularize stop-motion just as Disney was healing from its dark age.

The Nightmare Before Christmas happily shows how wonderful it is to be who you are--even if you are a nightmare.

Sources:

Greydanus SD. Stop-motion macabre. Catholic Digest. October 2014:82. Accessed September 23, 2020. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f5h&AN=98707128&site=ehost-live

Corliss R, Cole PE. A sweet and scary treat. TIME Magazine. 1993;142(15):79. Accessed September 23, 2020. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f5h&AN=9310057707&site=ehost-live

D’Alessandro A. “Nightmare” before & after. Daily Variety. 2006;292(51):A8. Accessed September 23, 2020. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f5h&AN=22389093&site=ehost-live

Moltenbrey K. Recurring Nightmare. Computer Graphics World. 2005;28(11):40. Accessed September 23, 2020. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f5h&AN=19270006&site=ehost-live

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/nightmare-before-christmas-poem_n_580f9209e4b02444efa594fa

https://www.wattpad.com/7767695-nightmare-before-christmas-original-poem-by-tim

DVD Extras

IMDB