The Historical Case of Women in Animation

As this year’s Animation April comes to a close, we thought we could discuss a topic that has been on our list for quite some time. During past years, we’ve covered the histories behind several animation studios like PIXAR, Laika, Cartoon Saloon, Amblimation, and Bluesky. We’ve discussed the history of animation, the rise of Walt Disney, and even the history behind a few specific animated films. And after poring over countless articles, watching several documentaries and DVD commentaries, and tracking down dozens of library books on the topic, we noticed that there was something–actually a lot of things–missing from the history of animation: women.

But it’s not as though women simply weren’t there in the early days of animation. In fact, women worked on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, one of the first full-length animated films. However, women were almost always relegated to ink and paint departments, which meant that they were responsible for creating animation cells based on drawings. It was an incredibly important part of the medium, but these women had no creative input on the final product. For many years, women were either consistently rejected from animation and story departments, or they were hired and not given credit for their work.

So today, we’re heading back in time to take a second look at the history of animation. But this time, we’re paying extra close attention to the people who, until recently, never got the credit that they deserved. We will list just some of the women whose influence on the medium can still be seen today, from the very first female animators to the women that helped make some of the first Disney Animated Classics. So grab some snacks and settle in, it’s time to learn about the history of women in animation!

Let’s go back to the beginning, shall we?

In 1906, J Stuart Blackton jump started the history of modern animation with The Humorous Phases of Funny Faces and Fantasmagorie, two pieces that are generally considered to be the first animated films. Shortly after, Windsor McCay expanded on the art form with character animation in his films featuring Little Nemo and Gertie the Dinosaur. Just a few years later, dozens of animation studios were popping up in New York City alone, and the era known as the “cartoon boom” began.

Windsor McCay would incorporate animation into his vaudeville performances as early as 1914. And recently, a historian named Mindy Johnson discovered that there was a woman who was doing something similar in the early 1920s.

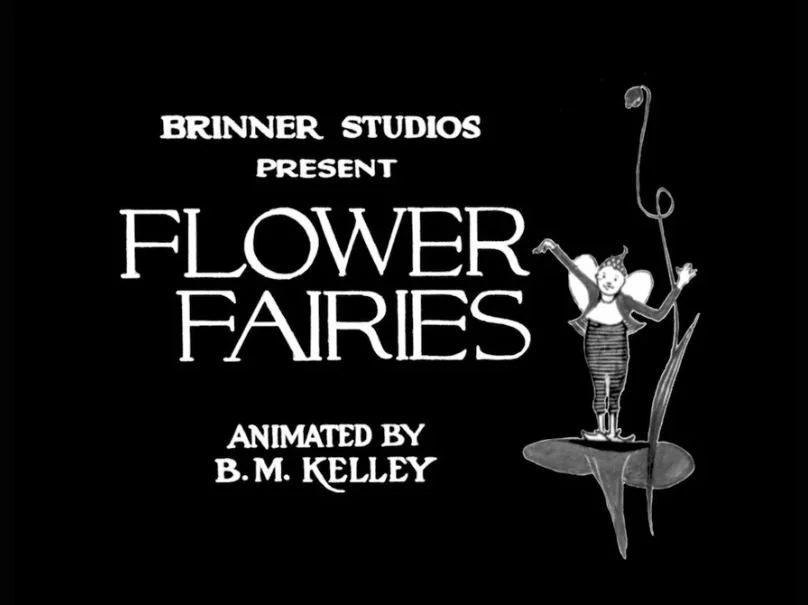

Bessie Mae Kelley was an animation pioneer that traveled vaudeville circuits, advertising herself as the only woman animator on tour. Kelley studied art at the New York Pratt Institute when she fell in love with film. She started out in the industry washing film cells and worked her way up. Eventually, she would be working among famed animators like Max Fleischer and Paul Terry. Kelley provided hand-drawn animation for Aesop’s Fables, a collection of animated shorts adapted from the collection of stories of the same name. Kelley created the first-ever mouse couple, and they appeared in Aesop’s Fables. According to historian Mindy Johnson, Walt Disney himself said that he was inspired to make animation that looked as good as the Aesop cartoons of the 1920s.

Bessie Mae Kelley animated and directed her own short films that are now considered to be the first movies to be hand-drawn and directed by a woman. While some have been restored, at least three of her films were lost due to corrosion. But, her remaining sketches prove that Kelley worked on productions that historians never even knew existed.

Historian Mindy Johnson discovered Bessie Mae Kelley’s history when she stumbled upon a newspaper article about a vaudeville act featuring “the only woman animator.” Mindy contacted other animation historians, asking if they had ever heard of this animator. One of Johnson’s colleagues showed her an illustration by animator Frank Mosher, who worked at Bray Studios (an early animation house that employed the Fleischer Brothers.) The image is of a group of men with one woman present that no one had previously identified. Johnson’s colleague told her that the woman was probably a cleaning lady or a secretary, but Johnson was able to match the woman in the picture to a photograph of Bessie Mae.

Determined to know more, Mindy Johnson tracked down relatives that held onto the animator’s letters and film reels. Johnson was able to get two of Kelley’s films restored, and premiered them at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in 2022. She hopes to release a book about Bessie Mae and possibly other early women animators whose work has been lost to time.

When asked about the meaning behind uncovering Bessie Mae Kelley’s work, Mindy Johnson told the American Film Institute: “We have a responsibility to change the history books. And history is exactly that – it is “his-story.” It is predominantly written about, preserved, archived and documented from a male perspective. There really were more women in front of and behind the camera than there are today, and there were more women working in animation than anyone ever realized.”

Lotte Reiniger working with panes of glass to bring her creations to life

In the early 1920s, when cartoon animation took the world by storm, Charlotte (Lotte) Reiniger was pioneering stop-motion animation in her birth country of Germany.

From a young age, Reiniger showed a lot of artistic promise. She was talented in Scherenschnitte (German for scissor cuts), and would cut silhouettes from paper. Reiniger wowed her friends and family with her art, putting on puppet shows with her work. Her career in film began when filmmakers recruited her to create title cards for silent films.

In 1918, Reiniger animated the rat sequences in The Pied Piper of Hamelin, a silent film directed by Paul Wegener. By the early 1920s, when Walt Disney was just beginning to form his own animation studio, Reiniger was directing stop-motion films starring her paper silhouettes. Many of these movies were based on fairytales, like Cinderella (1922).

In 1926, Lotte Reiniger directed one of the first-ever feature-length animated films: The Adventures of Prince Achmed. Her complex creations were unlike anything seen in film before, as Reiniger would even layer her silhouettes on panes of glass to give the film a layered look. This was nearly 10 years before the invention of the multiplane camera.

Silhouettes done by Lotte

A rejection letter from Walt Disney Pictures from 1938

Reiniger and her husband fled Germany just as Hitler rose to power, and settled in the UK after WWII. She continued to animate for several decades, directing more than 60 films (about 40 of which still remain). Reiniger is generally considered to be the first women animator, and was a true visionary in stop-motion animation. Her influence can still be seen in films today.

There are many records of pioneering women animators in the early 1920s and 30s, and we could never mention all of them. For example, there’s Valentina and Zinaida Brumburg, Jewish animators who began animating in the 1920s and continued to direct films for about fifty years. Another animator, Hermína Týrlová, is considered to be the mother of Czech animation, and directed over 60 stop-motion films throughout her career. We wish we could talk about everyone, but this is a topic that is just too vast for one episode.

In 1923, Walt and Roy Disney founded “Disney Brothers Studios.” The pair quickly became well-known in the animation industry with their silent Alice Comedies adapted from Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. But unlike today, Disney was not the most famous name in animation. Not yet, anyway.

Two years earlier in 1921, Max and Dave Fleischer started their own independent animation studios. They had been working for Bray Studios, and the pair had created a successful series of cartoons called Out of the Inkwell, which demonstrated Max’s invention of the rotoscope. Over the next decade, Max Fleischer would become a household name in the animation world, with his studio creating some of the most iconic cartoons of the 1930s such as Betty Boop and Popeye.

Just as Fleischer Studios was finding its footing, Lillian Friedman Astor began working for a small commercial studio. According to Astor, the company only had about 5 people, which gave her the opportunity to learn how to become an in-betweener. Intrigued by Walt Disney’s animation, Astor applied to work at his studio. She was rejected, and later said that the letter he sent her specifically stated that he did not hire women in creative departments.

In 1931, Astor landed a job with Fleischer Brothers Studios as an in-betweener. In 1933, she was promoted to animator and is believed to be the first American female animator to work for a major studio.

At about the same time, animator Laverne Harding received her first film credit while working for Walter Lantz Productions. She would be best known for animating the classic cartoon Woody the Woodpecker, which was also created by Lantz. Harding was good friends with Looney Tunes animator Tex Avery, and would work on some of his cartoons as well.

Astor worked on 42 films with the studio and was only credited for 6 of them. In 1937, she participated in a labor strike against Fleischer, which was the first major labor dispute in animation history (don’t worry, more followed). Astor joined the Commercial Artists and Designers Union as a result. Astor felt that management treated her badly afterwards, and the studio moved to Florida in an attempt to bust the union. Lillian Friedman Astor left Fleischer Brothers Studios shortly after their move, and was unable to find another job in the animation industry. She credited this to her part in the union, and to the fact that she was a woman.

In the mid to late 1930s, Walt Disney’s work began to stand out among the many popular cartoons of the time. His work quickly evolved from the quick movements of silly characters to a more realistic representation of animals, coupled with interesting stories.

Although Walt Disney was clear that he was not interested in hiring any women in the creative departments of his studio, a few trailblazing people were able to break down the barrier. They were met with sexism and gender discrimination, but eventually were able to earn the respect of their coworkers and pave the way for women in animation.

Bianca Majolie attended the same high school as Walt Disney. The two of them crossed paths, and Walt even doodled in Majolie’s yearbook. She went on to study composition, anatomy, and painting at Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, and began a career as a fashion designer. In the late 1920s, Majolie moved to New York and began designing brochures for JC Penney. In 1934, she saw one of Disney’s shorts for the first time, and realized the success that he had achieved. So, she wrote a letter to Walt Disney, requesting an interview.

Walt agreed to meet with Majolie, and he was impressed with her portfolio, including a self-produced comic strip about a girl trying to find a job during the depression. Walt offered Majolie a position in the story department.

As the first and only woman at the time, Majolie earned one fifth of the salary than that of the men. While she was paid $18, they were paid $100.

In Nathalia Holt’s book, The Queens of Animation, the author depicts the struggles that Majolie experienced while on the writing team at Disney. She would skip as many story meetings as possible because they were often humiliating. Majolie recalled one instance when Walt embarrassed Majolie in front of the team, and when she left the room, a group of male writers chased her to her office, banging on her door. Majolie cowered inside as the men broke down the door to further ridicule her.

Years later, Disney legends Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston credited Majolie for being the person that taught the department one of the most vital lessons in storytelling: “pathos gives comedy the heart and warmth that keeps it from becoming brittle.” They went so far as to say that they would not have been able to make any of their animated classics without learning this lesson.

Majolie shaped many of Disney Animation’s early classics, although her IMDB page hardly credits her on any of them. Because she was born in Italy and fluent in the language, she even translated the original Pinocchio to English so that the studio could adapt it. Majolie only worked for Disney for a few years. In 1940, she went on an extended vacation. Upon her return, she found that her desk had been cleared out and her position had been filled. She later married and opened an art gallery.

In 1936, Walt Disney hired Grace Huntington. She was an accomplished pilot, but unable to serve in the military because of her gender. Huntington faced similar discrimination as Majolie before her, and the women supported each other throughout their careers.

Huntington recalled her first story meeting, when a security guard would not allow her in the room because she was a woman. He told her that women were only part of the ink and paint departments. Eventually she was able to get inside, and when her colleagues saw her, they whistled.

Grace recalled Walt Disney telling her, “You know I don’t like to hire a woman in the story department. In the first place, it takes years to train a good story man. Then if the story man turns out to be a story girl, the chances are ten to one that she will marry and leave the studio high and dry, with all the money that had been spent on her training gone to waste and there will be nothing to show for it.”

Grace Huntington worked on many of the Mickey and Minnie Mouse cartoons and Silly Symphonies. She also advocated for Disney to hire more female writers, like Dorothy Ann Blank, who is the sole woman writer credited on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

Retta Scott studied at the Chouinard Art Institute, a leading art school in California that would eventually be absorbed into CalArts. Because of her passion for drawing animals, her professors urged the young artist to work for Disney. It wasn’t until Scott saw Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs that she was convinced to apply.

Scott’s mentor at Chouinard was a close friend of Walt Disney and recommended her for a job in the storyboard department, which was working on the film Bambi. She worked on a scene involving hunting dogs, and she made them into snarling, viscous beasts. The other animators were blown away by Retta’s technical skill, and she was offered the chance to animate the scene. Because of this, Retta Scott was the first woman to have an animation credit on a Walt Disney film.

Scott stayed on at Disney for a few years, becoming known as a specialist in animal drawing. Retta left Disney in 1946 to get married, but would do freelance work for the company for several years, illustrating many Disney Golden Books.

Former architect Sylvia Holland was hired to work in the story department of then Walt Disney Productions in 1939. She was the first woman to be a member of the Royal Institute of British Architects, and had been living in Vancouver with her family for several years before she relocated to southern California.

Holland was a widow and single mother of two children. Once she arrived in the US, she had to find a new career, because her degree wasn’t recognized in America. She began illustrating for Universal Pictures before she saw Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and knew that she wanted to work for the studio. She sought out jobs in animation across Hollywood in order to gain more experience. Eventually she applied to work with Walt Disney, who was impressed with her portfolio.

Holland was also an accomplished musician, and Walt Disney consulted her while choosing music for his Silly Symphonies and Fantasia. She storyboarded scenes for Make Mine Music and she created concept art for Bambi.

Concept art by Mary Blair for It’s a Small World

Although animator Mary Blair would go on to be one of the most influential animators in the early days of Disney animation, she was unsure about working at the studio.

Blair and her husband both worked for Ub Iwerks, a former chief animator at Disney who broke off from Walt’s studio and created his own. In 1940, Iwerks’ studio folded and Disney absorbed most of the company, and Mary Blair reluctantly accepted a job in Walt Disney’s story department.

Blair worked in Disney’s story department, but didn’t like working under Disney’s animators and quit. But, Walt was taken by Blair’s art and her unique style. He invited her and her husband Lee on the now-famous “Goodwill Tour” of South America.

The “Goodwill Tour” was an effort by the US government to combat Nazi influence in South American countries during WWII. Officials asked prominent entertainers to visit several South American countries and incorporate aspects of their culture in Hollywood films.

While on tour, Mary Blair was inspired by the beauty of each country, and had what she considered to be an artistic breakthrough. Walt Disney was impressed by her drawings, and offered Mary a role as an art supervisor for Saludos Amigos and The Three Caballeros.

Blair continued to work for Disney animation for several years, influencing films like Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland, and Peter Pan. She left Disney again in the early 1950s and created art for advertising campaigns, Broadway productions, and Golden Books. Ultimately she would return to Disney to design “It’s a Small World,” the company’s 1964 World’s Fair project that would eventually become a permanent fixture in the theme park. Mary Blair is often credited with bringing modern art to Disney, influencing the look and feel of not only the films, but the theme parks as well. Her bold color contrast and distinctive art style changed Disney–and animation–forever.

Concept art for Peter Pan by Mary Blair

This group of women are just a few of the early Disney animators that influenced the studio. In recent years, books like The Queens of Animation by Nathalia Holt and Ink and Paint: The Women of Walt Disney’s Animation shed light on the careers of early female Disney animators. However, you probably won’t find much mention of these artists in Walt Disney’s biographies. In fact, author Nathalia Holt even recalled seeing Mary Blair referred to simply as “Lee’s wife.”

It seemed that Walt Disney eventually came around on the idea of hiring women. In 1941 he was quoted saying, “The girl artists have the right to expect the same chances for advancement as men, and I honestly believe they may contribute something to this business that men never would or could.” Although some may find this quote dripping with condescension, it was still a progressive statement for the time.

Fifty-three years later in 1994, Walt Disney Animation hired Ellen Woodbury, its first woman supervising animator.

Beyond Disney animation, women animators continued to make film and TV history. Brenda Banks, one of the first black women in animation, started her career in the 1970s and worked on Ralph Bakshi’s satirical film Coonskin. Her other credits include Wizards, Lord of the Rings, various Looney Tunes projects, Tiny Toons, and The Pagemaster.

Banks began working in animation when there were very few black animators in the industry, and not much has changed. According to an article by Scripps News in 2022, only about 4% of animators are African American.

While there are more people of underrepresented genders and people of color in animation than before, there is still a huge lack of diversity. We can only hope that sharing the stories of the women that blazed the trail in early animation will inspire more artists to pursue the medium.

Women have always played a role in animation history. Today, their influence continues to inspire modern artists. We could spend hours discussing the accomplishments of the artists we mentioned today, and the ones that we left out. But since we can’t do that, we urge anyone interested in learning more to continue researching on your own. We will have our sources listed on our website, including Nathalia Holt’s book The Queens of Animation.

As our final Animation April comes to a close, it feels right to discuss these often overlooked stories from the medium’s history. We’re hopeful that the industry will continue to change and grow, allowing for even better and more inclusive storytelling.

And if anyone ever tries to tell you that you don’t belong in your chosen field, remember that Walt Disney and many others believed that women didn’t belong in animation, and how history has proven them wrong.

We’ve been studying movies and TV for over five years now, and this week’s topic reminded us that no matter how much you think you know, there’s always more to learn.